The following comment was sent to me by one of the blog readers.

Since it is too long to be posted on the comments' space, I am sharing it with you here:

June 15, 2013

“When there is a general change of condition of conditions, it is as if the entire creation had changed and the whole world been altered, as if it were a new and repeated creation, a world brought into existence anew.”

The Moquaddimah, Ibn Khaldun

Mir-Housein Mousavi, an Islamic revolutionary with left political sensibilities was the prime minster of Iran (1981-1989) during the Iran-Iraq war and was highly favored by the late leader of Iran Khomeini. He entered the political scene as a candidate of June 2009 presidential election against incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejat after two decades of absence starting with the end of the war and the death of the Revolutions’ late leader. During these years much had changed. The post-war “era of reconstruction” under the presidency of Hashemi Rafsanjani had sought to normalize the decade long revolutionary and war politics and economics. In the usual narrative, these years moved toward economic liberalization within the framework of rentier state and set the stage for the political demands of the Reform movement expressed by the 1997 election of Mohammad Khatami as the president. Khatami’s era marked a moment of political opening and emergence of a rich public discourse on the history of Islamic Republic, the ideals of the Revolution and diversion from its goals. Unlike Rafsanjani’s technocratic style of government, the newly elect reformist government and its powerful establishment conservative critics staged 8 years of antagonistic politics. Although these years have secured historical achievements that I will suggest below, Ahmadinejad’s 2005 election and the unification of conservatives and hardliners behind him demonstrated a certain fragility, if not defeat, of the reformist politics.

In 2009 Mousavi re-entered the political scene to restore aghlaniat, the rule of reason, to Iranian politics. He clamed that Ahmadinejad, a relatively recent addition to Iranian politics who was riding the wave of hardliner-conservative alliance against reformism, and more importantly the form of politics that he stood for, was the counterpoint to aghlaniat. He mobilized the history and the memory of the Revolution and the war and his personal association with these events against the dominant political voice within Iran during 2009. Unlike secular-liberal critics of the Iranian government, he challenged the very revolutionary and Islamic claims of the established power. Ahmadinejad’s main line against Mousavi was that he was the candidate of the old guard who similar to Khatami, was towing the line of Rafsanjani. Backed by the establishment himself – the supreme leader announced after the elections that his views were much closer to Ahmadinejad than the others - he was able to secure a second term in the disputed elections. His deceptive populism and international posturing which today proved short lived at best and hollow at worst proved triumphant. The state violently suppressed the ensuring protests and dismissed their demands as fitna – a theological-political formulation of secessionist politics. Four dark years where security quenched politics ensued. All the while the economy neoliberalized. These years were further darkened by sanctions and treat of military intervention in Iran. Today the world changed

Today, Hasan Rouhani, a mujtahed of the Qom seminaries who holds a PhD fromUniversity of Glasgow became the president elect of the 34 year old Islamic Republic. Rouhani has a thick resume of activism and occupation of highest ranks in the Revolution, the war and its aftermath, including the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council during Rafsanjani and Khatami presidency. He won the office of the president in the name of e’tedal and tadbir: moderation and wisdom. E’tedal can be captured closely by moderation, and in the context of Rouhani’s use, counters the extremism associated with hardliners and the conservatives. Indirectly, but very importantly, E’tedal is a response to a certain political Islamism of the hardliners within personal, social, and the international domain; a highly statist Islam that mobilizes the disciplinary and regulatory powers of the state in imposing its vision. Tadbir translates to wisdom, meditation, accounting for the consequences, long term evaluation and implies, specially in the context of Rouhani’s usage, aghlaniat: reason. Therefore, tadbir, like e-tedal, is formulation of a certain raison d'État, a certain statecraft that we can recognize, with Machiavelli or Foucault among others, as politics.

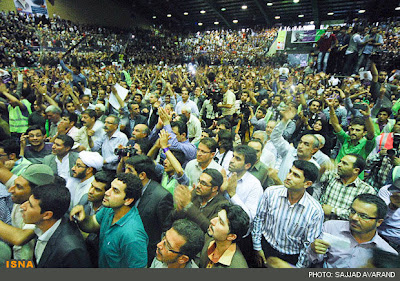

During his campaign, Rouhani moved significantly towards the political goals that are largely associated with the reform movement and the discontented parties of the last presidential election. He spoke against the security state, closure of spaces for political speech and action, and government infringements on personal spaces within the domestic domain while articulating a strong diplomacy in foreign affairs. He explicitly countered the foreign policy advanced by the government of Ahmadinejad and articulated by the Iran chief nuclear negotiator and the presidential hopeful Jalili as pandering to Islamic revolutionary slogans while receiving severe blows and passing them on the population (sanctions). Mohammad-Reza Aref, the only reformist candidate who had been able to pass through the Guardian Council pulled out in his favor and Rohani received strong endorsements from both Rafsanjani and Khatami. In his first address as the president elect a few hours ago, he recounted the names of Rafsanjani and Khatami on the national TV, a significant political speech act in so far as these two figures have been systematically tarnished by the hardliners and on the national TV since the 2009 elections.

Despite this association between Rouhani and the reform movement, and despite his explicit promise to do all he can to release political prisoners, and to undo the house arrest imposed on Mousavi, his spouse Zahra Rahnavard and Mehdi Karoubi (the other discontented candidate of the last election), I want to draw a different relation between Rouhani’s election and the reform movement more generally. Rouhani election is not the continuation of reform, but sublation of reform and a certain strand of hardline conservatism that has combated the reform since its inception in 1997. His election signals fruits of the reform movement, the triumph of its social and political discourse. It also signals, counter intuitively, an important developments among conservatives: the failure of the experience of Ahmadinejad or the form which it expresses, their failure to unite and their extreme fragmentation as the elections exposed, and more importantly, their inability to articulate an art of politics, a viable vision of coexistence and a statecraft Aref and the conservative Mohsen Rezai’s diagnosis of the hardliners during their campaign speaks to these developments among the conservative camp.

Rouhani, then, is not the middle ground between hardliners or reformists - a spatial formulation as if time is secular and history, thin. His election does not signal a “moderate” choice by the electorate, but a significant one in so far as it channels and builds upon the historical experience of the reformism and conservatism in the Islamic republic - their common forms, their particular achievements and defeats. Most importantly perhaps it speaks to the limit of a form of politics that is reduced to seizing the state and exclusion of political opponents. Perhaps this sublation is most clear in that Rouhani’s positions are only conceivable between the sign posts of Mousavi and the short-lived Khamenei-Ahmadinejad alliance: if it wasn’t for the radical position of Mousavi, Karoubi and the many others who paid and continue to pay a high price for making visible the law preserving violence of the state on the one hand, and those want-to-be-sovereigns within the hardline conservative camp, Rouhani would not be able to articulate the politics of e’tedal and tadbir.

In a field fraught with domestic instability, systematic political and religious suppression, “most crippling sanctions,” treat of war, and monopolization of the Iranian historical and popular desires by international war criminals outside Iranian borders, moderation and wisdom – politics - is given a chance. It’s a moment of ashtiy-e meli, national reconciliation. It is significant that this opportunity comes about not by increasingly ineffective and subverted revolutions, as the “Arab Spring” model is demonstrating, but through the vote. It remains to be seen what comes of this chance.

Perhaps we can hope that under the sign of e’tedal and tadbir, the excessively violent domestic antagonism relaxes in favor of a different form of engagement, or if we fail as the reformism and conservatism of the last two decades did, we fail better, and we fail to secure as significant of achievements as they did. We hope too, in the spirit of hope expressed in the vote, that this fragile play of forces in Iran does not flatten by international pressure on Iran. As Rouhani said in relation to his victory:

“A new opportunity has come about in the international scene for those who speak in the name of democracy, pluralism, free speech and truth, to bear witness to this popular achievement, engage with the Islamic Republic with respect and justice, and accept the rights of the Islamic Republic in order to hear the appropriate response, and work together to expand international relations based on mutual interests, peace, security and development in the region and in the world.”